Walking into Stash, Kim Adams’ winter 2024 exhibition at Hunt Gallery, felt less like entering a gallery show and more like stepping into a cluster of parallel universes — each one hand-built, layered, and humming quietly with its own internal logic. These works don’t perform for the viewer. They simply exist, and in that existence, they reveal something essential about the way Adams sees the world.

If I’m honest, this story doesn’t start at Hunt Gallery. It traces back to Art Toronto 2014, where I first encountered Adams’ Arrived. That sculpture made an impression I’ve never quite shaken — part surreal dreamscape, part social map, part puzzle. His work lodged itself somewhere in the back of my mind, waiting for the right moment to surface again.

That moment came at Art Toronto 2024, when I found myself face to face with Adams’ work once more — and with Daniel Hunt, the gallery owner representing it. Daniel spoke about the work with the kind of care that’s rare in the gallery landscape: not salesmanship, not hype, but genuine advocacy. Our conversation drifted easily from Adams’ career to the complexities of sculptural worldbuilding, and before I knew it, he’d invited me to see Stash, a show focused on Adams’ smaller-scale pieces.

I left the booth knowing I’d say yes.

And I’m grateful I did.

A Practice That Lives Between Life and Art

Kim Adams occupies a distinctive place in contemporary Canadian art, one shaped by humor, strange logic, and an undercurrent of social critique. What makes his work so compelling is the ease with which it moves between registers: whimsical and serious, playful and pointed, intimate and vast.

For decades, Adams has been crafting sculptural environments that feel like compressed versions of the world we live in. They’re packed with detail, populated with miniature figures, vehicles, and architectural fragments. Yet these are not simply models. They are worlds, and they are built with a knowing wink.

The humor in his work is never careless. It’s a tool.

And so is the satire.

And the seriousness.

Adams blends these modes until they become inseparable, giving the viewer permission to laugh, question, and reflect all at once.

This approach is especially visible in Stash, where the scale appears small but the ambition is anything but. Each piece is like a shard of society held up to the light, revealing both its beauty and its absurdity.

Small Worlds, Big Perpective

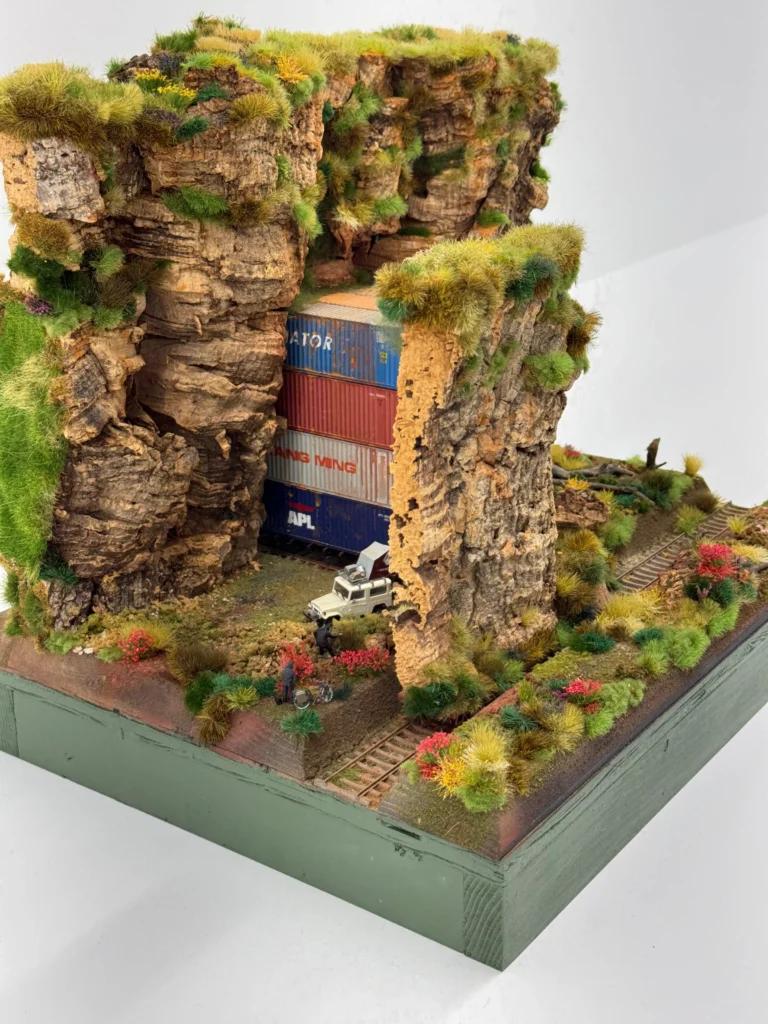

The works photographed above show the kind of scenes Adams constructs: a Land Rover dwarfed by rugged rock formations, shipping containers wedged improbably between cliffs, a pair of Volkswagen bus shells fused seamlessly into a mountainside. They look like fragments of forgotten stories, as if human civilization has continued to operate long after the world stopped paying attention.

Adams’ miniatures are not precious. They’re alive.

They don’t present polished fantasies but slightly skewed realities.

They’re detailed enough to feel familiar and strange enough to make you doubt your first reading.

This is where his strength lies: he takes the ordinary, trucks, trailers, figurines, shipping containers, and pushes them into contexts that feel both impossible and inevitable. The result is a kind of sculptural fiction. You read it like a story, even if you don’t know the plot.

Encountering the Artist

Meeting Kim Adams in person was one of the unexpected joys of the exhibition. For someone whose work has shaped and influenced contemporary sculpture for decades, he is deeply unpretentious. His presence is grounded, steady, almost quiet, and yet you feel the current of thought running just beneath the surface.

He spoke about his work the way a builder talks about a structure: plainly, practically, with an intuitive understanding of how every part fits together. There was no mystique, no posture, no art-world performance. Just a person who has spent a lifetime making things, worlds, really; and is still curious about where they might lead.

Afterward, I spent time leafing through the booklets on his career that Hunt Gallery had assembled. It was there that I revisited the iconic Bruegel-Bosch Bus (1996–ongoing), perhaps his best-known and most ambitious installation.

A 1960s Volkswagen bus transformed into a sprawling sculptural ecosystem, populated with dozens of scenes, references, and micro-narratives. Seeing that project contextualized the smaller works in Stash in a new way. They aren’t departures. They’re continuations, pieces of the same lifelong investigation into how we build, inhabit, and imagine worlds.

Scale as a Way of Seeing

What I felt most strongly while moving through Stash was Adams’ ability to minimize life without shrinking it.

Scale, in his hands, becomes a form of truth-telling.

When he condenses the world, he doesn’t simplify it.

Instead, he sharpens it.

A miniature scene becomes a place where you notice things you normally overlook, gestures, collisions, contradictions, the quiet comedy of daily life. There is something deeply human in that way of seeing. Something generous. Something gently critical.

You don’t stand in front of his work; you lean into it.

You look closer.

You adjust your perspective — literally and metaphorically.

That physical act of leaning in, of bringing your face inches from the scene, changes how you relate to it.

The work pulls you into its scale, and once you’re inside it, you start to recognize yourself.

Why This Exhibition Matters

Stash is a reminder that art doesn’t need to be monumental to be expansive. Adams’ miniature works hold the same charge as his larger installations, the same humor, the same satire, the same quiet seriousness, but on a scale that feels intimate, almost personal.

They operate like mirrors disguised as models.

And in a world that often feels overloaded, oversized, and overstimulated, there is something refreshing about art that requires us to go small in order to see big.

Walking out of Hunt Gallery, I felt a kind of grounded clarity. Adams’ work had done what great art often does: it rearranged the way I was looking at things. Not with grand statements or heavy symbolism, but with subtle shifts and gentle nudges, like someone tapping you on the shoulder to say, Look again. You missed something.

In a way, that’s the heart of Adams’ practice:

He asks us to look again, at the world, at ourselves, at the stories we build and stash away.

And if we’re willing to lean in, we might just find something we didn’t expect.

Canadian art, Kim Adams, Daniel Hunt, Hunt Gallery

I couldn\’t agree more! Your post is a valuable resource that I\’ll be sharing with others.

Thank you, for your kind words. I\’m committed to maintaining the quality of my posts.

I\’m so glad I found your site. Your posts are consistently excellent.